Last February, just three months ago, we updated an earlier article about the fast changes being experienced by the pay television industry, from a Latin American viewpoint. There were several world markets where linear pay television was losing subscribers at a fast pace –the U.S. and Brazil among then. It looked like 2021 would be a disruptive year, calling for a provocative moniker, something like “The Contents War Year”. You can consider it to be Episode 1 of an ongoing series.

Well, Episode 1 expectations fell short of what has been happening lately. The reasoning at that time what that the OTT field was becoming a bit crowded, after the announcement of the launching of several services to compete against incumbents Netflix and Amazon prime, plus early contenders DisneyPlus, AppleTV, HBO Max –in the U.S., the service is being launched in June in Latin America–, Paramount Plus and AVOD service PlutoTV.

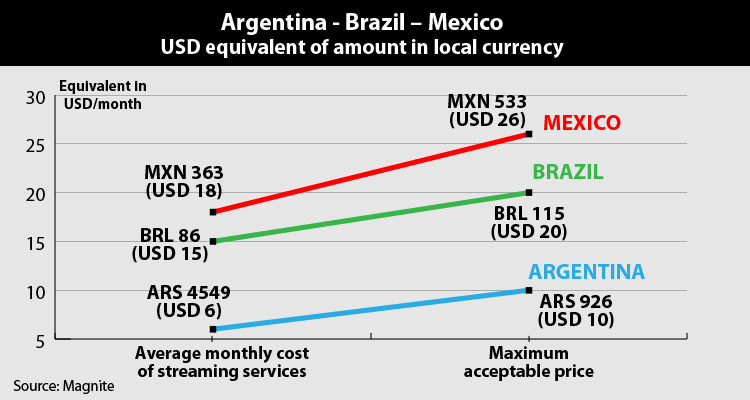

What has changed? On the one hand, fresh data arrived on the willingness attributed to users regarding how much money they accept spending on streaming services plus Internet access. And, how much more they are willing to pay out for a single service, prior to signing-off. Several reports point to between USD18 and USD26 as the maximum a Latin American average household will devote to this type of entertainment. This allows signingn up between three and four services. With Mexico, Brazil and Argentina currently having about thirty services each –most of them are available at various countries at the same time, at different prices— it is clear that for every winner there will be at least three losers. Of course, none of the Hollywood-studio-enclosed services wants to appear lagging their competition; this situation may call for some desperate measures in the twelve months gap from July 2021 to June 2022.

On the other hand, there will be increased pressure from the Virtual Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (vMVPDs), delivering linear channels and PPV content over the Internet and competing against cable operators and satellite-delivered services such as DirecTV and Sky. Industry analysts predict that these interlopers, made possible by the increase of Internet connectivity over cable television penetration, will attract price-sensitive customers. No less important, they represent a new revenue source to the programming contents, since they open room for series and movies already exploited on linear services and even free television, therefore extending the food chain by one additional step.

Last but not least, the results posted by Netflix for 1Q2021, with subscriber addition much lower than expected, have been understood by some analysts as the end of the Covid19-based 2020 “bonanza”. This comes at a time when other worries appear, among them “subscriber fatigue”, a consequence of the shorter lifetime binge-watched series provide. Here, the pandemic doesn’t help: it has delayed the production of a large quantity of content that was to be released in recent times and the near future. Considering that the Silicon Valley-based business model applied by Netflix calls for constant screen refreshment, and the limitations shown by the algorithms in use regarding what subscribers really would like to see, this is a question not to be overlooked by the major players.

For background on this issue, please check our earlier report: “2021, The Year of the Contents War”